Sumaya Kassim describes the challenges of trying to bring context to Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery

“The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us to temporarily beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change.” Audre Lorde, 1978

Earlier this year, I was part of a group of co-curators invited to set up an exhibition at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (BMAG) which would use the Museum’s collection to confront history in new and challenging ways. The attempt is worthy – reflective of movements like ‘Rhodes must fall’ and ‘why is my curriculum white’, which call for a radical reassessment of history, an awareness of how colonial processes impact our present times. However, the exhibition brought into focus an important question – one of whether large British institutions like BMAG can and should promote ‘decolonial’ thinking, or whether, in fact, they are so embedded in the history and power structures that decoloniality challenges, that they will only end up co-opting decoloniality.

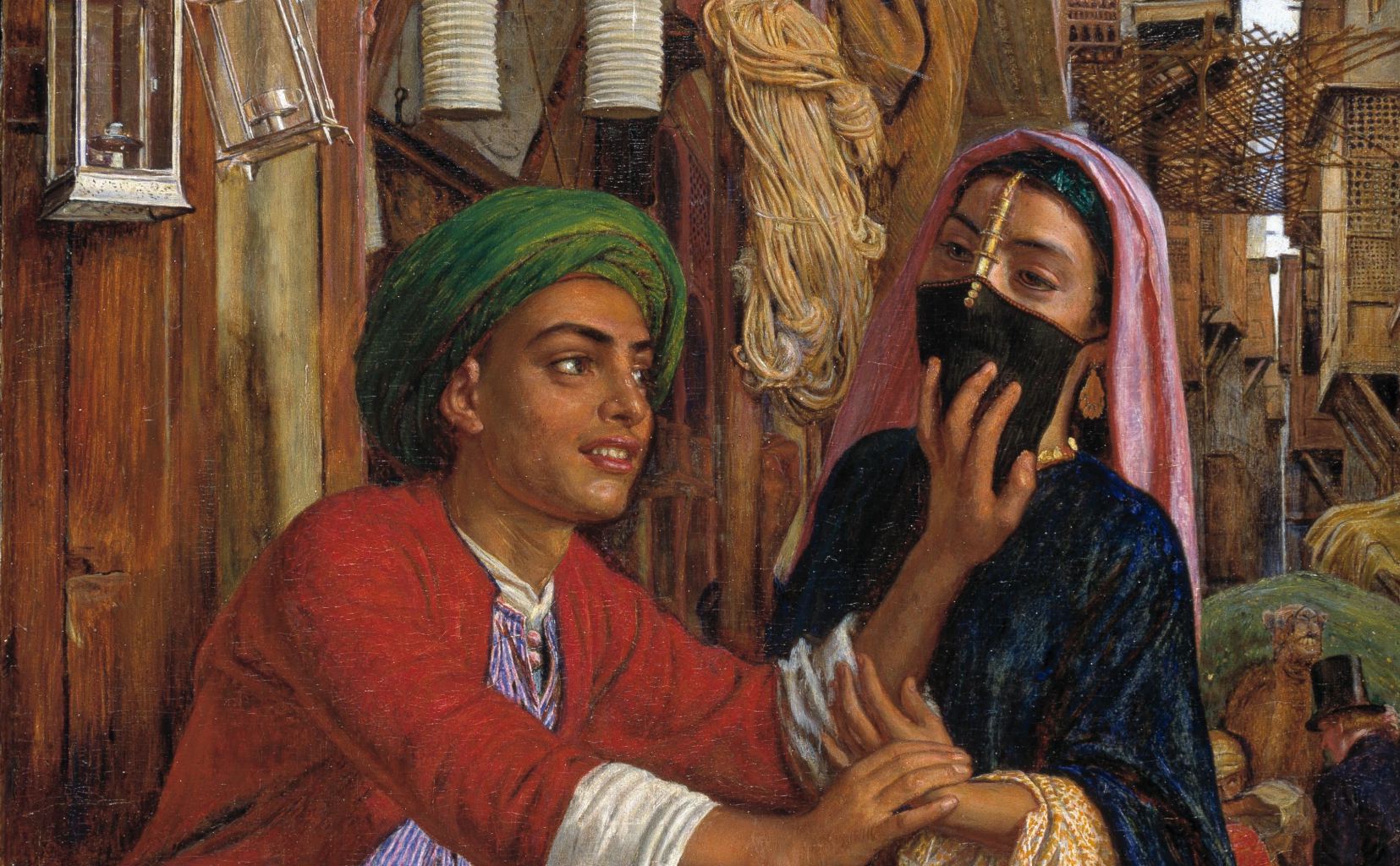

At the start of the project, we toured the permanent nineteenth-century exhibition together. One of the museum staff drew our attention to the labelling – the authorial voice of the museum – and the way that certain objects are deemed ‘valuable’ and therefore are placed in central positions, most of which are paintings by white men. In this time period, it seemed as though brown and black faces only appeared in Orientalist paintings, images which created a fantasy version of the rest of the world as underdeveloped, static, feminine. One such painting we saw languished in a corner, depicting a veiled woman whose mouth was literally being covered twice (by a veil and a man’s hand). Someone muttered: “I’m tired”, and everyone laughed.

At the start of the project, we toured the permanent nineteenth-century exhibition together. One of the museum staff drew our attention to the labelling – the authorial voice of the museum – and the way that certain objects are deemed ‘valuable’ and therefore are placed in central positions, most of which are paintings by white men. In this time period, it seemed as though brown and black faces only appeared in Orientalist paintings, images which created a fantasy version of the rest of the world as underdeveloped, static, feminine. One such painting we saw languished in a corner, depicting a veiled woman whose mouth was literally being covered twice (by a veil and a man’s hand). Someone muttered: “I’m tired”, and everyone laughed.

Museums are not neutral

Museums are not neutral in their preservation of history. In fact, arguably, they are sites of forgetfulness and fantasy. The way exhibitions are constructed usually assumes a white audience and privileges the white gaze. The white walls signified the choices of white people, their agency, their museum collections, and the endeavours of colonialists. To many white people, the collections are an enjoyable diversion, a nostalgic visit which conjures up a romanticised version of Empire.